In To Rip, Perchance to Burn and its prior posts in this series I talked about the various pieces of Mac software that can help you make an archival copy of a commercial DVD you own. Among these was MacTheRipper, an actual DVD extractor. It generally works OK, I find, but it so happens that the third or fourth DVD I tried to rip with it, Inside Man, gave it a bellyache.

About midway through the rip, MacThe Ripper complained that bad sectors had deliberately been coded into a VOB (Video OBject) on the DVD and asked me whether to delete or pad them. I chose pad. But MTR immediately got stuck, and no more progress was made. I had to quit MTR and start it again.

Before I did, I Googled "DVD VOB deliberate bad sectors MacTheRipper" and found some forum posts about the problem. One poster recommended to turn on "ARccOS" in MTR. That, I found, is done in the Mode panel (as opposed to the Disc panel) of the MTR window. You simply switch from "Full Disc Extraction" to "Full Disc (ARccOS) Extraction," and you turn on ARccOS.

What is ARccOS? This Wikipedia article says it's an extra dollop of copy protection some DVDs have. Which DVDs? See this list. (Yes, Inside Man is on the list.)

Unfortunately, although that strategy allowed MTR to finish the rip, at the end MTR still complained of bad sectors and suggested the resulting rip might be unplayable. And so it was. I'm trying the rip again, but I have little hope that MTR can cope with this DVD alone.

It's all about an arms race between the studios and the rest of the world. The rest of the world insist they have the right to make an archival copy of a DVD they legitimately possess, in case the original becomes unplayable. The studios say that opens the door to piracy and add ever new layers of copy protection. The purveyors of software like MacTheRipper try to overcome the new protection. In this case, with this DVD, it looks like MTR — at least, the version I have — hasn't quite succeeded.

The MTR version I have is the latest "official" release, 2.6.6 ... but it dates back to early 2005. The guru behind MTR is currently doing a version 3.0, which is in beta testing. Apparently the only way to obtain it is to donate money ... which I might do at some point. But not yet. I can wait.

Meanwhile, as a workaround I followed one forum poster's advice and input the output data of MTR into DVD2OneX. The latter is software that, mainly, further compresses a DVD so it will fit on a single-layer recordable disc. DVD2OneX also has the ability to create a dual-layer version of the original, but that is an option I haven't tried yet.

I told DVD2OneX to create a file set rather than a disc image — much less actually burn a disc — and it gave me a folder with VIDEO_TS and AUDIO_TS subfolders, just like on an actual DVD. At the end it warned me that it had detected 15,765 "mastering errors" in the input data, errors which it had "corrected" in the output — but that the result might still not "work properly."

I pointed Apple's DVD Player app at the VIDEO_TS produced by DVD2OneX and found that it can begin playing the movie seemingly without a problem.

What happened next was that I decided to copy the file set DVD2OneX had produced to a DVD-R and try playing that. Burning to DVD was a mistake, since the file set did not constitute a playable DVD.

The file set included two folders, VIDEO_TS and AUDIO_TS, but they alone don't seem to be enough to make a DVD playable as such. True, I could point Apple's DVD Player app at the disc's VIDEO_TS folder as "DVD Media" and the app would "play" the media files. Otherwise, though, I had a data-only DVD that would not play in a real DVD player.

So, next I tried using DVD2OneX to make a "disc image" on my hard drive. I chose the option to make a disc image for a dual-layer DVD, just to see what would happen. This resulted in an icon on the desktop that, when double-clicked, places a virtual disk volume on the desktop. That volume plays successfully in DVD Player as if it were an actual DVD in the optical drive.

The disk image icon apparently contains 6.85GB. So does the volume it mounts on the desktop when it is double-clicked. Strangely, this is the size of the VIDEO_TS folder alone. The AUDIO_TS folder appears to be empty! I can't explain that.

If I had a SuperDrive that would burn a dual-layer disc — which I don't — I could theoretically now use Disk Utility to burn my disc image into an actual disc. But of course if I had such a drive, I could have burned the disc directly from DVD2OneX.

As far as the playability of the result of using MacTheRipper and then DVD2OneX on Inside Man, there do seem to be minor issues. I'm only part way through watching the movie, but so far there seem to be at least two glitches in the playback. They're minor, as I say ... it's as if some frames were missing. I do find, though, that the scan forward and backward functions of the Apple DVD Player software don't work right with this disc image.

Accordingly, I have to conclude that the result of the rip is pretty good, but not perfect. Perhaps if I were to get the latest beta version of MacTheRipper, I could do better with Inside Man.

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

Friday, November 24, 2006

To Rip, Perchance to Burn

As of The Ripping Saga Continues, posted yesterday, I was still looking for a way to burn ripped DVDs onto recordable media.

The problem was that I could use MacTheRipper to rip a perfect, non-copy protected copy of a commercial DVD onto the hard drive of my new MacBook Pro. I could then play it in the DVD Player software Apple bundles in Mac OS X. Or I could simplify telling DVD Player what to do by using Matinee as a front end. But I had no way to transfer the VIDEO_TS folder and the other files and folders from the original DVD to a blank DVD-R.

Oh, in the extremely rare case of a commercial DVD with but a single layer's worth of data, 4.7GB or less, I could burn the ripped material into a single-layer DVD-R or DVD-RW directly from Finder. But most storebought DVDs are dual-layer jobs with more material than can be put on a single-layer DVD.

And unfortunately, my new (actually, refurbished) MacBook Pro is not the latest and greatest. It lacks a SuperDrive with dual-layer DVD+R burning capability.

Today I happened upon the Mac Rumors website and noticed that it boasts a tutorial on Backing up DVDs. That pointed me at the website of DVD2OneX, software (unfortunately not free software) that "shrinks" the data on a dual -ayer DVD so that it can fit on a single-layer disc.

Another such application, which I have not yet tried, is DVDRemaster from Metakine.

DVD2OneX is the Mac OS X version of the DVD2One software that runs on Windows. You can download and try it for a month for free, with few restrictions. I took advantage of the free trial and was so happy with the results I got that I immediately forked over the 39.99 euro asking price (a little over $53).

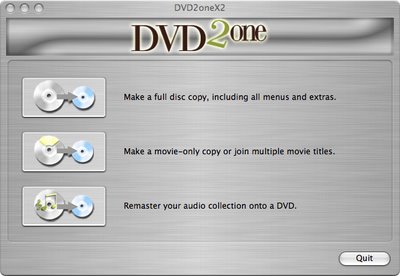

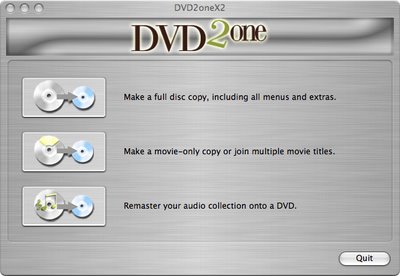

The initial DVD2OneX window looks like this (click to see a bigger image):

If you click the top graphic, you are invited to navigate to a VIDEO_TS folder that already exists on your hard drive. It will typically be in a containing folder whose other contents include an AUDIO_TS folder. The contents of the containing folder will have been previously ripped from the original DVD by MacTheRipper or a similar application.

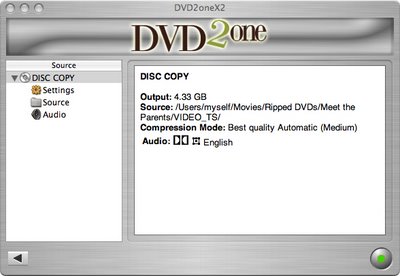

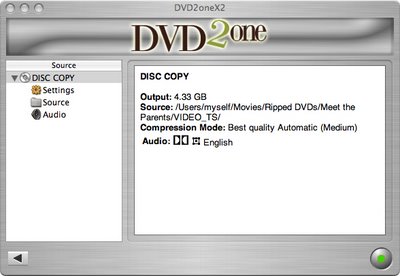

That brings up this window:

Clicking the green button at lower right, you will be permitted to choose to burn a DVD. (The other choices are to create either a disc image for later burning or just a set of files from which such a disc image can be constructed.) If you choose to burn, you'll be prompted to put a recordable DVD in your drive. You can give it any name you want. You will then observe DVD2One's progress in preparing for the burn (takes maybe 20 minutes on my Mac) and then actually doing the burn (goes slightly quicker).

At the end of the process, you'll have a new DVD whose main difference from the original is that its contents have been magically slimmed down to fit in 4.7GB. Exactly how DVD2One does this, I'm not quite sure. The burned disc has all the functionality — menus, special features, audio tracks, subtitles, etc. — of the original. It plays like a "real" DVD. Presumably, the video and audio have been further digitally compressed, which ought to produce lower picture quality. However, the PQ of the Meet the Parents test disc I made looked pretty darn good when played into my 61" HDTV.

And, yes, a DVD-R made in this way does seem to play back just fine in all of my DVD players and on both of my current Macs. No issues with disc readability that I ran into.

This means that Mac owners with the right version of the Mac OS X operating system (I'm using "Tiger" version 10.4.8) and a SuperDrive than can burn single-layer DVDs can arrange to make inexpensive archival copies of their DVDs that have very decent video quality indeed!

The problem was that I could use MacTheRipper to rip a perfect, non-copy protected copy of a commercial DVD onto the hard drive of my new MacBook Pro. I could then play it in the DVD Player software Apple bundles in Mac OS X. Or I could simplify telling DVD Player what to do by using Matinee as a front end. But I had no way to transfer the VIDEO_TS folder and the other files and folders from the original DVD to a blank DVD-R.

Oh, in the extremely rare case of a commercial DVD with but a single layer's worth of data, 4.7GB or less, I could burn the ripped material into a single-layer DVD-R or DVD-RW directly from Finder. But most storebought DVDs are dual-layer jobs with more material than can be put on a single-layer DVD.

And unfortunately, my new (actually, refurbished) MacBook Pro is not the latest and greatest. It lacks a SuperDrive with dual-layer DVD+R burning capability.

Today I happened upon the Mac Rumors website and noticed that it boasts a tutorial on Backing up DVDs. That pointed me at the website of DVD2OneX, software (unfortunately not free software) that "shrinks" the data on a dual -ayer DVD so that it can fit on a single-layer disc.

Another such application, which I have not yet tried, is DVDRemaster from Metakine.

DVD2OneX is the Mac OS X version of the DVD2One software that runs on Windows. You can download and try it for a month for free, with few restrictions. I took advantage of the free trial and was so happy with the results I got that I immediately forked over the 39.99 euro asking price (a little over $53).

The initial DVD2OneX window looks like this (click to see a bigger image):

If you click the top graphic, you are invited to navigate to a VIDEO_TS folder that already exists on your hard drive. It will typically be in a containing folder whose other contents include an AUDIO_TS folder. The contents of the containing folder will have been previously ripped from the original DVD by MacTheRipper or a similar application.

That brings up this window:

Clicking the green button at lower right, you will be permitted to choose to burn a DVD. (The other choices are to create either a disc image for later burning or just a set of files from which such a disc image can be constructed.) If you choose to burn, you'll be prompted to put a recordable DVD in your drive. You can give it any name you want. You will then observe DVD2One's progress in preparing for the burn (takes maybe 20 minutes on my Mac) and then actually doing the burn (goes slightly quicker).

At the end of the process, you'll have a new DVD whose main difference from the original is that its contents have been magically slimmed down to fit in 4.7GB. Exactly how DVD2One does this, I'm not quite sure. The burned disc has all the functionality — menus, special features, audio tracks, subtitles, etc. — of the original. It plays like a "real" DVD. Presumably, the video and audio have been further digitally compressed, which ought to produce lower picture quality. However, the PQ of the Meet the Parents test disc I made looked pretty darn good when played into my 61" HDTV.

And, yes, a DVD-R made in this way does seem to play back just fine in all of my DVD players and on both of my current Macs. No issues with disc readability that I ran into.

This means that Mac owners with the right version of the Mac OS X operating system (I'm using "Tiger" version 10.4.8) and a SuperDrive than can burn single-layer DVDs can arrange to make inexpensive archival copies of their DVDs that have very decent video quality indeed!

Thursday, November 23, 2006

The Ripping Saga Continues

In the last episode ("More on Ripping DVDs") I talked about making bit-by-bit, file-by-file copies of commercial DVDs, sans copy protection, using Matinee and MacTheRipper.

Matinee is a so-called "VIDEO_TS launcher." It allows you with just a click or two of the mouse to launch the DVD Player app and play any DVD that you've previously ripped to your hard drive. VIDEO_TS is the name of the folder on a DVD that contains video information. A companion folder, AUDIO_TS, holds all the audio information. When a "DVD extractor" such as MacTheRipper "extracts" the video and audio information from the shiny disc in your optical drive, it makes duplicate VIDEO_TS and AUDIO_TS folders on your hard drive. You tell Matinee (by setting its Preferences) where to find their containing folder, and from that time on Matinee (via DVD Player) will play them at your beck and call.

Here's Matinee's simple user interface:

In theory you can go on to burn a homebrew DVD with the contents which MacTheRipper has "extracted" from the original DVD. The DVD you'd burn would lack the usual copy protection, regional coding, and other roadblocks to playing or otherwise manipulating its content. This is not something Matinee or MacTheRipper do themselves. Rather, you do it in Finder.

But, as I said in my earlier post, most commercial DVDs contain more than the capacity of a single-layer DVD, which is 4.7 gigabytes. They're accordingly dual-layer: 8.5GB. So you need to burn them to a dual-layer DVD. Therein lies a potential hangup.

At the time I wrote the last post (yesterday) I didn't know for sure whether dual-layer (DL) recordable DVDs even exist. Turns out they do. They're a variation of the DVD+R format, where the "+R" differentiates this format from DVD-R (which doesn't yet offer dual-layer recordability).

I also didn't know if my new MacBook Pro (15" screen, 2.16GHz CPU) could record them. Turns out it can't. This comes as a surprise. When I bought the MacBook Pro — I was picking from the refurbished models available at the Apple Store at bargain prices — I thought I was buying the "Apple MacBook Pro Core 2 Duo 2.16MHz 15-Inch" model. I didn't realize this was actually a "Core Duo" and not the newer 2.16MHz "Core 2 Duo" model (note the extra digit "2"). The latter can write DVD+R DL discs; the former can't.

I also didn't know if my new MacBook Pro (15" screen, 2.16GHz CPU) could record them. Turns out it can't. This comes as a surprise. When I bought the MacBook Pro — I was picking from the refurbished models available at the Apple Store at bargain prices — I thought I was buying the "Apple MacBook Pro Core 2 Duo 2.16MHz 15-Inch" model. I didn't realize this was actually a "Core Duo" and not the newer 2.16MHz "Core 2 Duo" model (note the extra digit "2"). The latter can write DVD+R DL discs; the former can't.

You can find specs on these and other Mac models at EveryMac.com. It's easier to find such information there than at the Apple website.

Quite frankly, I find that name-change subtlties such as "Core Duo" and "Core 2 Duo" are a bit much to keep track of these days. Still, I find it hard to blame Apple for the name game; it's only trying to keep up with fast-paced changes in what's it's possible to offer its customers. I should have been paying closer attention, that's all.

Nor do I blame Apple's "special deals on refurbished Macs" outlet site. It truly does offer great prices on like-new gear. Which gear it has seems to change from day to day, which makes good sense. If the site doesn't happen to have a particular model available today, it's not listed on the page. Check it out.

Still and all, I ended up with less than the state-of-the-art Mac that I thought I was getting, simply because I failed to pay close attention to the difference between "Core Duo" and "Core 2 Duo" — which, technically, seems to have to do not so much with processor speed as with processor efficiency. The Core 2 Duo has a more efficient design than the mere Core Duo did, which means that CPU throughput is greater even when nominal processor speed is identical (in my case, 2.16MHz).

In my experiments yesterday I used Apple's Activity Monitor utility and discovered that HandBrake uses a percentage of the CPU of something like 175% (!). I imagine this is what having a Core Duo CPU (of any design) buys you: the ability to approach 200% CPU utilization. There are in effect two processors inside the Core Duo, both running in parallel. If an application is constructed to take advantage of that duality — as HandBrake seems to be — it can approach 200% on the software "speedometer." Cool.

The MacBook Pro I have, while not the latest-and-greatest, does seem to be lightning fast compared with the other four or five Macs I have previously owned. Apple made a wise decision, abandoning the old PowerPC processor family. It takes only about an hour to rip a movie on DVD.

The new Core Duos with "Intel Inside" can do Windows! All you need is a legal copy of Windows XP — or Windows 2000 or 3.1, or any of several versions of Linux, for than matter — and Parallels Desktop for Mac ($79.99). This Macworld review says Parallels works fine! And, unlike Apple's own Boot Camp product (reviewed here), with Parallels you don't need to reboot to switch between Mac OS X and Windows. Double cool.

The new Core Duos with "Intel Inside" can do Windows! All you need is a legal copy of Windows XP — or Windows 2000 or 3.1, or any of several versions of Linux, for than matter — and Parallels Desktop for Mac ($79.99). This Macworld review says Parallels works fine! And, unlike Apple's own Boot Camp product (reviewed here), with Parallels you don't need to reboot to switch between Mac OS X and Windows. Double cool.

More later.

Matinee is a so-called "VIDEO_TS launcher." It allows you with just a click or two of the mouse to launch the DVD Player app and play any DVD that you've previously ripped to your hard drive. VIDEO_TS is the name of the folder on a DVD that contains video information. A companion folder, AUDIO_TS, holds all the audio information. When a "DVD extractor" such as MacTheRipper "extracts" the video and audio information from the shiny disc in your optical drive, it makes duplicate VIDEO_TS and AUDIO_TS folders on your hard drive. You tell Matinee (by setting its Preferences) where to find their containing folder, and from that time on Matinee (via DVD Player) will play them at your beck and call.

Here's Matinee's simple user interface:

In theory you can go on to burn a homebrew DVD with the contents which MacTheRipper has "extracted" from the original DVD. The DVD you'd burn would lack the usual copy protection, regional coding, and other roadblocks to playing or otherwise manipulating its content. This is not something Matinee or MacTheRipper do themselves. Rather, you do it in Finder.

But, as I said in my earlier post, most commercial DVDs contain more than the capacity of a single-layer DVD, which is 4.7 gigabytes. They're accordingly dual-layer: 8.5GB. So you need to burn them to a dual-layer DVD. Therein lies a potential hangup.

At the time I wrote the last post (yesterday) I didn't know for sure whether dual-layer (DL) recordable DVDs even exist. Turns out they do. They're a variation of the DVD+R format, where the "+R" differentiates this format from DVD-R (which doesn't yet offer dual-layer recordability).

I also didn't know if my new MacBook Pro (15" screen, 2.16GHz CPU) could record them. Turns out it can't. This comes as a surprise. When I bought the MacBook Pro — I was picking from the refurbished models available at the Apple Store at bargain prices — I thought I was buying the "Apple MacBook Pro Core 2 Duo 2.16MHz 15-Inch" model. I didn't realize this was actually a "Core Duo" and not the newer 2.16MHz "Core 2 Duo" model (note the extra digit "2"). The latter can write DVD+R DL discs; the former can't.

I also didn't know if my new MacBook Pro (15" screen, 2.16GHz CPU) could record them. Turns out it can't. This comes as a surprise. When I bought the MacBook Pro — I was picking from the refurbished models available at the Apple Store at bargain prices — I thought I was buying the "Apple MacBook Pro Core 2 Duo 2.16MHz 15-Inch" model. I didn't realize this was actually a "Core Duo" and not the newer 2.16MHz "Core 2 Duo" model (note the extra digit "2"). The latter can write DVD+R DL discs; the former can't.You can find specs on these and other Mac models at EveryMac.com. It's easier to find such information there than at the Apple website.

Quite frankly, I find that name-change subtlties such as "Core Duo" and "Core 2 Duo" are a bit much to keep track of these days. Still, I find it hard to blame Apple for the name game; it's only trying to keep up with fast-paced changes in what's it's possible to offer its customers. I should have been paying closer attention, that's all.

Nor do I blame Apple's "special deals on refurbished Macs" outlet site. It truly does offer great prices on like-new gear. Which gear it has seems to change from day to day, which makes good sense. If the site doesn't happen to have a particular model available today, it's not listed on the page. Check it out.

Still and all, I ended up with less than the state-of-the-art Mac that I thought I was getting, simply because I failed to pay close attention to the difference between "Core Duo" and "Core 2 Duo" — which, technically, seems to have to do not so much with processor speed as with processor efficiency. The Core 2 Duo has a more efficient design than the mere Core Duo did, which means that CPU throughput is greater even when nominal processor speed is identical (in my case, 2.16MHz).

In my experiments yesterday I used Apple's Activity Monitor utility and discovered that HandBrake uses a percentage of the CPU of something like 175% (!). I imagine this is what having a Core Duo CPU (of any design) buys you: the ability to approach 200% CPU utilization. There are in effect two processors inside the Core Duo, both running in parallel. If an application is constructed to take advantage of that duality — as HandBrake seems to be — it can approach 200% on the software "speedometer." Cool.

The MacBook Pro I have, while not the latest-and-greatest, does seem to be lightning fast compared with the other four or five Macs I have previously owned. Apple made a wise decision, abandoning the old PowerPC processor family. It takes only about an hour to rip a movie on DVD.

The new Core Duos with "Intel Inside" can do Windows! All you need is a legal copy of Windows XP — or Windows 2000 or 3.1, or any of several versions of Linux, for than matter — and Parallels Desktop for Mac ($79.99). This Macworld review says Parallels works fine! And, unlike Apple's own Boot Camp product (reviewed here), with Parallels you don't need to reboot to switch between Mac OS X and Windows. Double cool.

The new Core Duos with "Intel Inside" can do Windows! All you need is a legal copy of Windows XP — or Windows 2000 or 3.1, or any of several versions of Linux, for than matter — and Parallels Desktop for Mac ($79.99). This Macworld review says Parallels works fine! And, unlike Apple's own Boot Camp product (reviewed here), with Parallels you don't need to reboot to switch between Mac OS X and Windows. Double cool.More later.

Wednesday, November 22, 2006

More on Ripping DVDs

In Ripping DVDs with HandBrake (Part 2) I said MacTheRipper was next on my list of experiments with ripping DVDs. MacTheRipper is software that imports files from a DVD into a folder on a Mac's hard drive.

A DVD is nothing more than a bunch of computer files and folders. If it weren't for copy protection, you could just copy them to your hard drive and play them from there, using Apple's DVD Player application. In fact, I'm told that simple method actually works with some DVDs.

MacTheRipper, on the other hand, copies all DVDs, without copying the copy protection. It also defeats the regional coding which keeps you from playing DVDs from foreign lands.

MODmini's "Saving DVDs as VIDEO_TS Files" page (part of its "How-To: Turn Your Mac mini into a DVD Jukebox" article) advises to use Matinee along with MacTheRipper. Matinee front-ends your folder(s) of ripped DVDs and makes playing any of the movies in Apple's DVD Player a one-click affair. Matinee simply fires up MacTheRipper when you tell it you want to rip a new DVD.

MODmini's "Saving DVDs as VIDEO_TS Files" page (part of its "How-To: Turn Your Mac mini into a DVD Jukebox" article) advises to use Matinee along with MacTheRipper. Matinee front-ends your folder(s) of ripped DVDs and makes playing any of the movies in Apple's DVD Player a one-click affair. Matinee simply fires up MacTheRipper when you tell it you want to rip a new DVD.

I downloaded both of these items of free software. Once I dealt with some minor perplexities, both worked straightforwardly. So far I've ripped both discs of Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Ring Extended Edition and also Meet the Parents Bonus Edition. All the ripped versions seem to play in DVD Player just as if they were on the original disc. You get the whole DVD menu system intact, allowing you to choose language/subtitle options, special features, etc., as well as the main film.

The next thing to try would seem to be burning the ripped files to a do-it-yourself DVD-R and seeing if that disc works in various standalone and computer DVD players. But I ran into a snag there: the files won't all fit on a 4.7GB single-layer DVD-R! Since the original DVDs are dual-layer, it would seem that I need to use dual-layer DVD-Rs. I don't at this point even know if they exist though, or whether my MacBook Pro's internal SuperDrive could burn them.

Until I find my way down that path, more now on using HandBrake to rip and compress a DVD all in one fell swoop.

I am continuing to experiment with Handbrake's various options for choosing:

The object of the game is to make HandBrake's output file as small as possible, consistent with "good enough" picture quality (PQ). HandBrake decodes the video on a DVD and re-encodes it in a different codec. The codec used on a DVD is always a form of MPEG-2. That used by HandBrake's output files is a form of the newer, better MPEG-4.

The main idea here is that MPEG-2 compression is inefficient and results in big files with high bitrates. MPEG-4 compression can produce nearly as good PQ with smaller output files and lower bitrates. The AVC/H.264 codec (which is one of HandBrake's two choices, in addition to MPEG-4) is actually a high-class version of MPEG-4; it supposedly does even better.

Within either of these codecs in HandBrake you can choose a target file size or an average bitrate, resulting in a constant bit rate (CBR) in the output encoding. If you want a variable bit rate (VBR) so that more bits will be allocated to scenes that are harder to encode and fewer bits will be wasted on easy-to-encode scenes, choose a "constant quality" percentage — instead of a target size or bitrate, that is.

I've been trying 50% "constant quality" (CQ50) AVC encoding with pretty good results: tolerable picture quality, fairly compact (but widely variable, depending on the movie) file sizes.

I've also been trying using a bitrate of 1000 kbps with 1-pass MPEG-4 encoding. Comparing the results in QuickTime for Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Ring Extended Edition Part 2, I believe a CBR MPEG-4 encoding at about 990MB for the output file looks better (!) than a VBR AVC encoding that produces a 1.15GB file. At least in some scenes — those in which there is a somewhat uniform medium-to-dark gray backdrop, mainly — there is less of a tendency for solid blocks of a single color (visible "macroblocks") to show up and flicker on and off, thereby harming the naturalness of the scene.

There are many variables here. Using a bitrate of 1000 kbps with 1-pass MPEG-4 encoding, I have tried both the XviD encoder and the FFmpeg encoder in HandBrake. The results are very, very close both in PQ and file size ... but I think the XviD encoder does just a smidgen better with at least one critical scene.

One of the things that has gotten in my way in making these evaluations is that iTunes' Full Screen mode for viewing movies seems to exacerbate the inherent macroblocking in the recordings. A movie viewed in Fit to Screen mode may look pretty good in iTunes, but switch to Full Screen mode and the overall brightness scale is boosted in a way that brings out the macroblocks. This anomaly does not happen in the equivalent modes in QuickTime Player.

A good way to evaluate the various HandBrake encoding options is to view their respective outputs side-by-side in QuickTime Player Fit-to-Screen windows. When you come to a problematic scene in one window, pause it and cue up the same scene in the other window(s). Then compare.

More later.

A DVD is nothing more than a bunch of computer files and folders. If it weren't for copy protection, you could just copy them to your hard drive and play them from there, using Apple's DVD Player application. In fact, I'm told that simple method actually works with some DVDs.

MacTheRipper, on the other hand, copies all DVDs, without copying the copy protection. It also defeats the regional coding which keeps you from playing DVDs from foreign lands.

MODmini's "Saving DVDs as VIDEO_TS Files" page (part of its "How-To: Turn Your Mac mini into a DVD Jukebox" article) advises to use Matinee along with MacTheRipper. Matinee front-ends your folder(s) of ripped DVDs and makes playing any of the movies in Apple's DVD Player a one-click affair. Matinee simply fires up MacTheRipper when you tell it you want to rip a new DVD.

MODmini's "Saving DVDs as VIDEO_TS Files" page (part of its "How-To: Turn Your Mac mini into a DVD Jukebox" article) advises to use Matinee along with MacTheRipper. Matinee front-ends your folder(s) of ripped DVDs and makes playing any of the movies in Apple's DVD Player a one-click affair. Matinee simply fires up MacTheRipper when you tell it you want to rip a new DVD.I downloaded both of these items of free software. Once I dealt with some minor perplexities, both worked straightforwardly. So far I've ripped both discs of Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Ring Extended Edition and also Meet the Parents Bonus Edition. All the ripped versions seem to play in DVD Player just as if they were on the original disc. You get the whole DVD menu system intact, allowing you to choose language/subtitle options, special features, etc., as well as the main film.

The next thing to try would seem to be burning the ripped files to a do-it-yourself DVD-R and seeing if that disc works in various standalone and computer DVD players. But I ran into a snag there: the files won't all fit on a 4.7GB single-layer DVD-R! Since the original DVDs are dual-layer, it would seem that I need to use dual-layer DVD-Rs. I don't at this point even know if they exist though, or whether my MacBook Pro's internal SuperDrive could burn them.

Until I find my way down that path, more now on using HandBrake to rip and compress a DVD all in one fell swoop.

I am continuing to experiment with Handbrake's various options for choosing:

- codecs

- encoders within codecs

- target file sizes, average bitrates, or "constant quality" percentages

The object of the game is to make HandBrake's output file as small as possible, consistent with "good enough" picture quality (PQ). HandBrake decodes the video on a DVD and re-encodes it in a different codec. The codec used on a DVD is always a form of MPEG-2. That used by HandBrake's output files is a form of the newer, better MPEG-4.

The main idea here is that MPEG-2 compression is inefficient and results in big files with high bitrates. MPEG-4 compression can produce nearly as good PQ with smaller output files and lower bitrates. The AVC/H.264 codec (which is one of HandBrake's two choices, in addition to MPEG-4) is actually a high-class version of MPEG-4; it supposedly does even better.

Within either of these codecs in HandBrake you can choose a target file size or an average bitrate, resulting in a constant bit rate (CBR) in the output encoding. If you want a variable bit rate (VBR) so that more bits will be allocated to scenes that are harder to encode and fewer bits will be wasted on easy-to-encode scenes, choose a "constant quality" percentage — instead of a target size or bitrate, that is.

I've been trying 50% "constant quality" (CQ50) AVC encoding with pretty good results: tolerable picture quality, fairly compact (but widely variable, depending on the movie) file sizes.

I've also been trying using a bitrate of 1000 kbps with 1-pass MPEG-4 encoding. Comparing the results in QuickTime for Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Ring Extended Edition Part 2, I believe a CBR MPEG-4 encoding at about 990MB for the output file looks better (!) than a VBR AVC encoding that produces a 1.15GB file. At least in some scenes — those in which there is a somewhat uniform medium-to-dark gray backdrop, mainly — there is less of a tendency for solid blocks of a single color (visible "macroblocks") to show up and flicker on and off, thereby harming the naturalness of the scene.

There are many variables here. Using a bitrate of 1000 kbps with 1-pass MPEG-4 encoding, I have tried both the XviD encoder and the FFmpeg encoder in HandBrake. The results are very, very close both in PQ and file size ... but I think the XviD encoder does just a smidgen better with at least one critical scene.

One of the things that has gotten in my way in making these evaluations is that iTunes' Full Screen mode for viewing movies seems to exacerbate the inherent macroblocking in the recordings. A movie viewed in Fit to Screen mode may look pretty good in iTunes, but switch to Full Screen mode and the overall brightness scale is boosted in a way that brings out the macroblocks. This anomaly does not happen in the equivalent modes in QuickTime Player.

A good way to evaluate the various HandBrake encoding options is to view their respective outputs side-by-side in QuickTime Player Fit-to-Screen windows. When you come to a problematic scene in one window, pause it and cue up the same scene in the other window(s). Then compare.

More later.

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

Ripping DVDs with HandBrake (Part 2)

Here's the second installment in my Ripping DVDs series. The first was Ripping DVDs with HandBrake (Part 1). HandBrake is free software your Mac can use to rip DVDs into computer files for later play without the original DVD.

Here's the second installment in my Ripping DVDs series. The first was Ripping DVDs with HandBrake (Part 1). HandBrake is free software your Mac can use to rip DVDs into computer files for later play without the original DVD.At the MODmini website I found this helpful how-to on HandBrake and like topics, in addition to the three tutorials cited in the earlier post. (The HandBrake stuff is on the "Converting DVDs for QuickTime Playback" page of the four-page article.)

The MODmini turorial talks about doing just what I want to do: turn the Mac mini I intend to purchase into a discless "DVD jukebox." The same site also offers "DVD Kiosk How-To," discussing the ins and outs of using the Mac mini as a simple DVD player, complete with a functional remote control, to play optical discs directly.

I am still fooling around with HandBrake in an effort to figure out just how I want to use it. One option would be to rip each DVD movie into as small a computer file as will yield tolerable picture quality (PQ) on playback. The enemy of picture quality is digital video compression. Too much compression causes picture artifacts: digital "noise," pixellation, macroblocking, etc. But as you reduce the degree of compression to minimize artifacts, the file size explodes.

Going for small file sizes results in PQ compromises. I experimented yesterday with the idea of using a target size that will fit on a writeable CD, and I found the strategy to be somewhat viable but problematic. My idea was that squeezing files down to CD size will allow me to store a lot more movies on my hard drive and will let me optionally archive them to CD.

A recordable CD (a CD-R or CD-RW) holds 650 or 700 megabytes, depending on the CD. When I set HandBrake to use a target size of 700 MB, it actually produced a file a bit larger than that — too large for my purposes. Re-ripping with a 650-MB target size gave me a file comfortably under 700 MB. However, the 700-MB CD-RWs I first tried to use to test burning my HandBrake files seemed to cause unrecoverable problems or have fatal defects in them, so I re-ripped yet again with a 600-MB target size, for a file under 650 MB that would fit onto a 650-MB CD-R.

I had in earlier experiments determined that, for any given target file size, HandBrake's AVC/H.264 video "codec" ("coder-decoder") gives better PQ results that its alternative, the MPEG-4 codec — at the expense of longer ripping times.

I don't really understand that lingo, but I believe the "AVC/H.264" codec implements Part 10 of the MPEG-4 standard for video encoding and compression. The "MPEG-4" codec implements Part 2 of the same standard. Any AVC/H.264 or Part 10 codec is supposedly "capable of providing good video quality at bit rates that are substantially lower (e.g., half or less) than what previous standards [including MPEG-4 Part 2] would need." So Part 10 is better than Part 2 at any give bitrate — though slower. From now on I'll refer to these two codecs in HandBrake as simply MPEG-4 (for Part 2) and AVC (for Part 10).

So my under-650-MB experimental file used AVC, not MPEG-4. The actual AVC "encoder" choice that I selected in HandBrake was "x264 (Main profile)," not "x264 (Base profile)." The ability to select among different encoders within a given codec is not one I fully understand the ramifications of yet. In earlier experiments I have found the Base Profile AVC encoder generates slightly larger files than the Main Profile encoder.

That ripped-DVD-file-copied-to-CD proved to work fine on my MacBook Pro, the fast new Intel-based computer on which I made it. But when I tried it in iTunes on my older, slower iMac, playback stuttered. Yet playback in QuickTime on the same iMac went fine. iTunes likewise stuttered when I copied the AVC file from the CD to its hard drive and played the copy. It also stuttered when, via my AirPort Extreme network, I played the original file that was on the MacBook's hard drive into iTunes on the iMac.

My conclusion: my iMac's 1-GHz PowerPC CPU just isn't fast enough to cope with AVC video in iTunes, though it unaccountably does fine with the same AVC video in QuickTime. The actual source of the AVC video file — the iMac's own hard drive, a CD, the network — doesn't matter.

On the other hand, the iTunes/iMac combintion does just fine with MPEG-4 video rips. Still and all, for now I'm sticking with the higher quality of AVC and expecting to play the results either on a fast Mac or in QuickTime on my slower Mac.

Even though the PQ is better with AVC than MPEG-4, for any given target file size, HandBrake offers you ways of improving it even more. One is to abandon the target file size in favor of a target average bitrate in kilobits per second. The two are joined at the hip. If you input a target size, the bitrate (though grayed in the HandBrake panel) changes accordingly, and vice versa. Both methods use a constant bitrate; they provide two different ways to determine what that bitrate will be. You can set the bitrate you want directly. Or you can set the file size and let HandBrake figure out what bitrate goes with it.

But as the "Converting DVDs for QuickTime Playback" page of the MODmini DVD Jukebox article says, a constant bitrate (CBR) limits the quality of scenes that need higher bitrates. With a variable bitrate (VBR), "the movie takes more space where more things are happening, and less space when not much is going on."

You are telling HandBrake to use VBR when you choose "constant quality" video instead of a target file size or bitrate. When you do that, you get to adjust a slider to set the quality you want. It's graduated in percentages, where 100% gives you the best possible PQ, using the most hard drive space. The default setting is 50%. MODmini says each additional 10% above that roughly doubles the file size.

Right at this minute, I'm experimenting with constant-quality AVC and MPEG-4 rips. My attempts to encode full-length movies at CQ100 (i.e., a constant quality of 100%) have thus far caused mysterious HandBrake failures toward the end of the ripping process, generating huge unopenable files. Possibly the file sizes became too big for Mac OS X to deal with.

When I switched to experimenting with ripping just a single chapter of a DVD, CQ100 worked fine, at least with MPEG-4 video. The result looks pretty good, too ... but so does CQ90 or even CQ80 with AVC video. I'm currently experimenting with CQ80 AVC. Specifically, I'm ripping Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Rings, Pt. 1, from the Special Extended DVD Edition of that already-classic film. It's the first 1 hour, 45 minutes, 30 seconds of the movie on the disc.

Well, that didn't work! HandBrake went through its connipitions and combobulations for an hour or two, got to where its progress bar reached 100%, and vanished without a trace, leaving me with another unusable output file, this one of some 5.5 GB. Again, I think these may be file sizes too large for Mac OS to handle. Or maybe HandBrake can't handle them when it tries to finish up — during the delay after the progress bar reaches 100% before HandBrake is done with the rip.

It occurs to me, though: do I really care whether HandBrake can produce files that aren't much smaller than the content of the original DVD? The dual-layer Fellowship DVD contains 6.9 GB of material. That includes several soundtracks, several separate video and audio files for the individual chapters of the movie, multiple menus, multiple subtitles, a lot of control information for the DVD player to figure out how to use the disc, etc. When I rip it in HandBrake, I filter out a lot of that information.

For example, when I choose a subtitle or captioning option — since I'm hard of hearing — the captions get "burned into" the movie. In playing the ripped copy, I can't turn them off. As such, they don't represent "extra" information, as they do on the DVD.

Likewise, all information about chapter stops is lost in the ripped copy of the DVD.

So a rip that exceeds 5 GB while giving me lower picture quality and less playback flexibility isn't all that wonderful. If I want to give up 5 GB of hard drive space, I might as well give up 6.9 GB and have all the picture quality and flexibility of a DVD.

One simple way to do that that sometimes works (see the MODmini "Introduction" page) is to open the DVD in Finder as if it were an ordinary hard drive or folder and drag its VIDEO_TS and AUDIO_TS folders to the Desktop, or to one of your own folders. Copies of the original DVD's folders will be made on your hard drive; it takes several minutes. Then, fire up DVD Player and, per MODmini, "select Open VIDEO_TS Folder in DVD Player's File menu. Navigate to the copied VIDEO_TS folder and your movie will play just as if from the DVD. Easy, free, and no additional software is needed."

Alas, with some DVDs it may be that simple, but "the Finder-copy method may not work on all DVDs, or on all computers. We’ve successfully tested many, many DVDs, but we’ve also seen Finder fail to copy some and DVD Player refuse to play others." With Fellowship, I can copy the necessary folders, but DVD Player won't play them, due to copy protection.

That's where MODmini's "Saving DVDs as VIDEO_TS Files" page comes in. It's method, more general if more complex, relies on Matinee and MacTheRipper software.

"MacTheRipper streamlines the process of saving your DVDs to your hard drive. Not only does it slice and dice exactly which of the DVD’s contents should be saved, but it can also reset region encoding, remove Macrovision copy-protection, and perform a number of other advanced tasks."

Then it's Matinee's turn. "Matinee provides a convenient, TV-suitable interface for selecting the movies on your hard drive, and watching them via DVD Player. It comfortably fills the gap between the Finder and DVD Player, and is easily controlled with a remote."

I've downloaded MacTheRipper (great name!) but haven't played with it yet. That's next on my agenda. Stay tuned!

Sunday, November 19, 2006

Ripping DVDs with HandBrake (Part 1)

HandBrake is free software you can use on your Mac to "rip" DVDs into computer files for viewing as:

HandBrake is free software you can use on your Mac to "rip" DVDs into computer files for viewing as:- Front Row movies

- QuickTime movies

- iTunes movies

- iPod movies (video iPod required)

If you hook your Mac to an HDTV, the ripped DVD files can be viewed on its large screen. With networked Macs the ripped files can be viewed on a different Mac than the one where the files reside.

HandBrake is not hard to download and launch. It's user interface is fairly simple, basically a single panel containing a variety of options (click image to enlarge).

But figuring out which way to use those options to rip your DVDs with HandBrake isn't easy.

I've been making some experiments with HandBrake, about which I'll report soon, and I've found some helpful tutorials to help me through my perplexity. One of these is at iLounge.com. Another is from MethodShop.com. A third is from FreeSMUG.org. Check 'em out.

More later.

Saturday, November 18, 2006

The Convergence Scene

In Media Center Mac Mini for My Bedroom? (Part 1) and Media Center Mac Mini for My Bedroom? (Part 2) I spoke of equipping a Sharp AQUOS LC-37D90U 37" flat-panel LCD HDTV I intend to buy with a "media center PC": a Mac mini, suitably enhanced to capture and archive programs from cable TV. In my Apple's Forthcoming iTV post I discussed iTV, the pre-announced $299 product from Apple which can route media files from computers and their networks over into a TV and its associated audio gear. With iTV and a wireless or wired home computer network, you'd be able to point an ultra-simple remote control at an equally simple box next to your TV and summon up movies, music, photos, and any other sort of digital media files that your computer houses or can access.

In Media Center Mac Mini for My Bedroom? (Part 1) and Media Center Mac Mini for My Bedroom? (Part 2) I spoke of equipping a Sharp AQUOS LC-37D90U 37" flat-panel LCD HDTV I intend to buy with a "media center PC": a Mac mini, suitably enhanced to capture and archive programs from cable TV. In my Apple's Forthcoming iTV post I discussed iTV, the pre-announced $299 product from Apple which can route media files from computers and their networks over into a TV and its associated audio gear. With iTV and a wireless or wired home computer network, you'd be able to point an ultra-simple remote control at an equally simple box next to your TV and summon up movies, music, photos, and any other sort of digital media files that your computer houses or can access.All this is part of the "convergence" of home computers and home theaters. Convergence is the natural by-product of the fact that everything is now digital. Movies and other video items are digital on DVD, HD DVD, and Blu-ray; on over-the-air (OTA) digital broadcast TV; on digital cable; on satellite TV; on the Internet, if not always legally; at the Apple iTunes Store; on iPods, BlackBerrys, and cell phones, etc., etc., etc. Ditto, TV shows, podcasts, movie trailers, YouTube uploads, and so on — they're all available digitally. Photo albums and home movies, too, are computerized and alive in the digital domain.

For audio-only media it's the same deal. CDs are digital. So are the MP3 files you rip from CDs in iTunes or in like computer applications. So are the songs you download from the iTunes Store, or wherever.

As for home-theater gear: most of the TVs you can buy today are either flat panels or "microdisplay" front/rear projectors. Both create their images digitally. And audio/video receivers in home-theater sound systems can take in, manipulate, and optionally output audio streams that are wholly in the digital domain.

In fact, you can divide most digital entertainment content today into just four categories:

- content on home computers and their networks

- content online, including the World Wide Web and the iTunes Store

- content on non-computer feeds coming into your home, such as OTA, cable, and satellite TV, satellite radio, etc.

- content on hard media like CDs and DVDs

iTunes, with its CD-ripping functionality, brings some category-4 content — specifically, CDs — into your computer environment, including your iPod, as category-1 content. (You can use third-party rippers like HandBrake to capture DVDs.) The iTunes software also taps into a fair amount of the category-2 content: the sort available online at the iTunes Store.

The big problem, convergence-wise, is with category-3 content. How do you bring over-the-air, cable, and satellite TV, satellite radio, and so forth into your computer environment, where it lives as files holding category-1 content that can be bridged to your home theater by the likes of iTV.

I have no personal experience with satellite radio and can't comment on it. My interest is mainly in the "TV taps" that you can turn on and off in your home: specifically, the "cable-TV tap."

When you hook the wire that brings cable TV into your home to a suitable device such as a digital cable box — or a "digital cable ready" television equipped with a cable tuner and a CableCARD — you can turn on the tap at will and get any and all of the programming you've signed up for. Some if it is still analog, while much of it is now digital. Some of the digital cable channels are standard-definition, some are high-def.

You can even record cable programming that you are authorized to receive by saving it on a digital video recorder (DVR) built into the cable box. If you go to the trouble and expense of leasing a DVR box from the cable company, such temporary recordings of (even high-def) digital programming, made for the sole purpose of time-shifting the viewing experience, are perfectly legal.

Likewise, you can legally use a TiVo Series 3 HD-DVR to do your time-shifting. Put one or two CableCARDs from your cable company into this TiVo, and you can have it do what the DVR in the cable box would ordinarily do: capture SDTV analog, SDTV digital, and HDTV digital cable programming for later enjoyment. In the case of SDTV analog content, the programs are digitized and compressed by the TiVo itself. With SD and HD digital content, the TiVo just saves the original digital program stream as is.

Likewise, you can legally use a TiVo Series 3 HD-DVR to do your time-shifting. Put one or two CableCARDs from your cable company into this TiVo, and you can have it do what the DVR in the cable box would ordinarily do: capture SDTV analog, SDTV digital, and HDTV digital cable programming for later enjoyment. In the case of SDTV analog content, the programs are digitized and compressed by the TiVo itself. With SD and HD digital content, the TiVo just saves the original digital program stream as is.I don't think, however, that you can export the digitized-or-saved content from either a cable DVR box or a TiVo to a computer. Oh, you can play that content back into a TV-capture device in a computer and try to capture it that way. The playback all too often is analog, coming out of the cable box or TiVo along component-video, S-Video, composite-video, or 75-ohm "RF" wires.

The best of these analog options is component video; it would be nice to find a TV-capture device for a computer that digitizes it, compresses it, and archives it. As yet, though, the only TV-capture devices I know of for the Mac or the PC take only S-Video, composite-video, or 75-ohm "RF" input. (One such product, which I intend to investigate thoroughly, is the ConvertX PX-TV402U PVR from Plextor, shown at left.)

The best of these analog options is component video; it would be nice to find a TV-capture device for a computer that digitizes it, compresses it, and archives it. As yet, though, the only TV-capture devices I know of for the Mac or the PC take only S-Video, composite-video, or 75-ohm "RF" input. (One such product, which I intend to investigate thoroughly, is the ConvertX PX-TV402U PVR from Plextor, shown at left.)None of these connection types other than component video has enough bandwidth to carry high-definition images without losing resolution. All introduce noise and artifacts into the picture. So ... it beats me why there are no component-video TV-capture devices for the Mac.

Better still would be devices that could capture digital video at 720p or 1080i, and even at 1080p, with no intermediate detours into the analog domain. Ideally, it would have to work with both broadcast (OTA) and cable, which unfortunately encode the signal differently. Optionally, it would also work with satellite TV, with yet a different encoding.

For the Mac, Elgato Systems' EyeTV Hybrid (shown in a laptop) already seems to do the job with OTA digital TV, but not with digital cable. For the latter, a CableCARD would be needed. Elgato has told me via e-mail that "It would be nice to have a product that supports the CableCARD however it is too early in the development of the CableCARD to be viable. At the moment, there are no such products available."

For the Mac, Elgato Systems' EyeTV Hybrid (shown in a laptop) already seems to do the job with OTA digital TV, but not with digital cable. For the latter, a CableCARD would be needed. Elgato has told me via e-mail that "It would be nice to have a product that supports the CableCARD however it is too early in the development of the CableCARD to be viable. At the moment, there are no such products available." CableCARD is a thin device that slips into a TV set (or another device like a TiVo) and allows the TV's internal cable-TV tuner to gain access to the channels the cable company authorizes you to receive — including, of course, digital channels. The cable company brings the CableCARD to your home, installs it, and authorizes it. You (or the cable guy) just plug the wire that would normally go to a cable box into the TV itself.

CableCARD is a thin device that slips into a TV set (or another device like a TiVo) and allows the TV's internal cable-TV tuner to gain access to the channels the cable company authorizes you to receive — including, of course, digital channels. The cable company brings the CableCARD to your home, installs it, and authorizes it. You (or the cable guy) just plug the wire that would normally go to a cable box into the TV itself.Then you don't need the cable box — unless, that is, you depend on interactive, two-way cable-box communications for getting a program guide, pay-per-view, or video-on-demand. CableCARD can't deal with those three functions. If you can dispense with them, you can tell the cable guy who delivers the CableCARD to take his cable box and put it where the sun don't shine.

The next revision of CableCARD will eliminate the two-way interactivity problem. Unfortunately, CableCARD 2.0 will not be backward compatible with the CableCARD-equipped TVs of today. Those TVs are merely "digital cable ready." TVs expected in 2007 0r 2008 — the ones with the new CableCARD 2.0 slots — will be "interactive digital cable ready."

(An editorial aside: a few years back, the Federal Communications Commission in Washington, D.C., mandated that cable companies offer CableCARDs to their customers and that TV makers put CableCARD slots in their TVs. Score one for "government interference in the marketplace." CableCARDs are a goo idea. But the commissioners were too namby-pamby to mandate the equivalent of CableCARD 2.0 right off the bat, ensuring that there would one day be a clumsy, confusing, consumer-angering transition between the original CableCARD and the newer, non-crippled one. That day is going to be here soon. Score one for the marketplace libertarians who would have shown the FCC the door in the first place.)

(Note also that there is already a move afoot to make even CableCARD 2.0 obsolete. It's called OpenCable. Here is it's website.)

Why are we having such a long wait for everything to fall into place, convergence-wise? Espeically with regard to category-3 "TV tap" content, there is no good solution yet for capturing and archiving it. Why not?

You can, if you like, blame the typically long gestation period for any cutting-edge technology. You can blame the Feds either for not exercising strong enough dominion over teh technology or getting in its way, depending on your political persuasion. But part of the blame stems from the legitimate anxiety that content owners have over digital rights management (DRM).

DRM is, in essence, copy protection that can be supervised digitally — plus, of course, access authorization. Do you have legitimate access to a digital cable channel such as Fox Digital or HBO? DRM decides. Can you make a temporary time-shifting copy of, say, 24 or The Sopranos? DRM decides. Can you make a permanent archival copy on a computer hard drive or a home-brew CD? DRM decides. Can you upload your copy onto the Internet for other people to download? DRM decides.

DRM extends to "hard" digital media such as DVDs, HD DVDs, and Blu-ray discs. CDs don't use it — which is why they were so easily "napsterized." The digital copy protection on DVDs has, meanwhile, been compromised, which is how HandBrake allows you to create legal archival copies of your DVDs.

DRM also extends to online content. If you buy a song at the iTunes Store, it plays back only on your authorized computers, or on the iPods sync'ed to them.

DRM also extends to over-the-air digital TV broadcasts. By law, anybody can access OTA content, but can that content be recorded? If so, how may those recordings be distributed and used? Here is where the infamous "broadcast flag" rears its ugly head. Until struck down by a federal court, a mandate by the FCC was bout to require that TV makers build into their TVs the ability to respond to a set of bits (a "flag") in a digital broadcast that could (optionally, at the behest of program originators) block or hamper digital recordings of the content in the home of the user.

Digital content, unless access or copying is blocked somehow, moves easily from device to device — say, from a Blu-ray disc player or a cable box to a TV. If the receiving device can capture it in the form of a digital recording, content owners would like to be able to limit such recording activity to that which is legal under copyright law. Modern digital copy protection schemes typically allow them to place their digital content into one of three categories:

- copy freely

- copy one time

- copy never

A "copy freely" program sent out by a cable-TV company can be copied at will as many times and for as many generations as you like. A "copy never" program cannot be copied, period. A "copy one time" program lets you make as many first-generation copies of it as you like, but the copies will be flagged "copy no more," or "no more copies," so copies of the copies cannot be made.

The same kind of flags can be used with content on HD DVD and Blu-ray discs. Plus, copy protection flags can be brought into play whenever you try to transfer digital content in your home from one device to another in your home: over a computer network, via Firewire, via DVI or HDMI, etc. If you try to transfer a "copy never" program, the source and receiving device may collaborate to keep you from doing so. The same with a "copy no more" program.

At this point, I don't think anybody really knows how well DRM and copy management work in the real world. There are two potential problem areas. One, DRM might be too "leaky"; it might let copyright violations occur too easily. Two, DRM might be over-strict and keep consumers from exercising their legitimate rights. In fact, it's possible that DRM might be both too leaky in some respects and too strict in others.

We have yet to find out how well DRM works because today, before we run into DRM, we typically run into "brute force" methods of copy protection.

If you have a cable box today that has a built-in DVR, chances are it simply does not provide any way to export a digital signal — with the obvious exception of HDMI, or its predecessor, DVI. HDMI/DVI use uncompressed digital video signals only; these signals require too much bandwidth to be shunted into a recording device.

Recorders need digital video that is still compressed, the way it comes into the cable box before it is decoded and sent out over HDMI to the TV. Some cable boxes do offer the ability to send compressed digital video out over Firewire to an outboard recording device. I have heard surprisingly little about this, and I do not know whether my own cable boxes can do it. As yet, I have no recording device which could capture the Firewire output.

That's exactly what I would like my anticipated Mac mini to do. Now you know why I feel like a pioneer, when I'd much rather feel like a settler!

Friday, November 17, 2006

Apple's Forthcoming iTV

As I said in Media Center Mac Mini for My Bedroom? (Part 2), I'm looking to feed a Sharp AQUOS LCD flat panel TV with input from a Mac-based media center, probably a Mac mini. In researching that plan, I learned that Apple has a pre-announced product, code-named iTV, that may fit into my scheme.

Here is an article about iTV. The article includes photos, such as the one at left, of the giant screen behind Apple CEO Steve Jobs during his presentation at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts Theater in San Francisco, California on September 12, 2006.

Here is an article about iTV. The article includes photos, such as the one at left, of the giant screen behind Apple CEO Steve Jobs during his presentation at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts Theater in San Francisco, California on September 12, 2006.

iTV's details are sketchy. We know that iTV:

iTV's network connectivity will allow its use as a front end to access recorded media files — movies, music, etc. — on the Internet or on a home computer network, whether wired, wireless, or a combination of the two. My particular network could build in a Mac mini, but it wouldn't need to, since I already have other Macs on a wireless AirPort network.

The iTV itself would serve as my network's video connection to my flat-panel TV, ideally via its HDMI port. It would provide an audio connection to a separate sound system, ideally via either HDMI or the digital optical audio output.

Another article about iTV appears in Wikipedia (with a link to this page offering streaming video of Jobs' full Yerba Buena presentation). The article mentions rumors "that the iTV will sport other features, such as a built in DVR feature, or even Live TV, but this is highly unlikely. Like the iPod, the iTV will start out as a mainly recorded media [gathering] device" — that is, on a home computer network.

In Media Center Mac Mini for My Bedroom? (Part 1) I looked at two TV-related Mac products from Elgato Systems, EyeHome and EyeTV Hybrid. The first of these looks like a direct competitor to iTV — whose advent will probably spell curtains for it, since EyeHome is, like iTV, a networked media-client hub. The second Elgato product, EyeTV Hybrid, offers the live TV and DVR features the Apple product apparently lacks. It is not itself network-oriented.

When you think about it, then, iTV (like Elgato's EyeHome) is all about gathering, accessing, and playing existing media content from many disparate network sources seamlessly — a worthy goal.

But the EyeTV hardware, in its Hybrid form or as EyeTV 250, is all about capturing live content piped into the home via cable or satellite or obtained over the air via an antenna. This function is one which Apple has not addressed.

iTV seems very carefully designed not to be usable as a high-def digital video recorder — by running a Firewire or USB 2.0 cable to it from, say, a digital cable box.

Some digital cable boxes (I am told) can output HD video content in digital form on Firewire, potentially allowing it to be recorded on external devices such as DVD recorders. I've never tried it, so I don't know its ins and outs. Nor have I heard of any cable boxes that output USB 2.0. But iTV is seemingly not going to be in the business of allowing digital cable-TV content to be archived on it, or even via it to its back-end computer network.

It would of course be nice if iTV could record digital 720p and 1080i HDTV programming as such. Or, if not capturing it directly on its own hard drive, at least passing it along to other computers on a home network.

But, alas, no. iTV has no intrinsic video input capability. It can retrieve already recorded video material from a home network or from the Internet, but it cannot capture live TV.

Even if an external TV-capture device like EyeTV Hybrid could be connected to iTV's USB 2.0 port, as if to enable the iTV to capture a television signal, how would the requisite EyeTV software be installed on Apple's iTV?

And even if Apple's iTV could somehow host Elgato's EyeTV software, Elgato's EyeTV hardware can't accept digital cable input ... not without the signal already having been converted to merely standard-def analog by a separate cable box.

Specifically, EyeTV lacks the ability to accept TV signals in digital form directly from the 75-ohm wire that feeds a cable box. It does not have an onboard cable-TV tuner. Nor does it accept a CableCard for decoding digital cable input. Nor does it have a Firewire input to allow it to receive a digital signal output from a standalone cable box.

In fact, Elgato tech support informs me: "There are no products for the Mac or PC that can natively decode the encrypted signal from the cable company." That's where CableCard support could come in handy. As far as I know, most or all digital cable channels are encrypted to ensure that only authorized cable boxes (or CableCards) can receive them. This includes premium channels like HBO, high-definition channels, and in fact any and all digital channels that are not part of the cable company's basic tier of service.

My own cable company, Comcast Cablevision of Baltimore County, Maryland, charges extra for all digital channels, since it basic tier channels are still all-analog. So all digital cable channels that are available to customers require decoding.

Currently, no products for either the Mac or PC will do that. That may change someday. If it does, I could conceivably make a Mac mini into the equivalent of a TiVo Series 3 HD-DVR, but with the ability to permanently archive high-def and standard-def TV content in its original form.

There's also the problem of bandwidth, though. Broadcast 720p and 1080i signals require up to 19.2 Mbps. They're only lightly digitally compressed — though cable companies typically squeeze broadcast digital channels down, bandwidth-wise, yet more.

Suppose you could somehow input 1080i at up to 19.2 Mbps into iTV and wanted to record it on a Mac mini, to which the iTV wirelessly networks via one of Apple's AirPort 802.11g products. 802.11g (also called WiFi) can run as fast as 54 Mbps, with a "typical" rate of 25 Mbps. That conceivably could be fast enough for shunting a single HDTV signal around a home network — assuming optimal wireless reception conditions. So, technically speaking, it might be possible for Apple or a third party to enhance iTV to serve as an HD-DVR — a high-definition digital video recorder.

Hence it would be nice if digital cable boxes and satellite receivers offered USB 2.0 output of their digital video signals for use by the likes of iTV. Then any digitally compressed TV signal received by the cable box might be exported into iTV, where software such as Elgato's EyeTV could capture it, either on iTV itself or elsewhere on the home network, via 802.11g.

That would be nirvana, but it's not apt to happen. Think of the copy-protection issues. Though you have a legal right to archive, for you own enjoyment and use, TV programs you legitimately receive, content providers are not about to make it easy for you. We've all heard about the "broadcast flag" that might one day be inserted into digital TV programs so you can't copy them. There are other flags in digital television that can do the same sort of thing. I've yet to hear whether, or how, they're in use today, but you can bet they'll sprout right up once a product something like iTV makes digital-TV capture simple for the masses.

Meanwhile, the prerecorded content Steve Jobs has in mind for iTV play is mainly what's available at Apple's iTunes Store. There you can now get songs, as always, plus movies, TV shows, podcasts, music videos, and movie trailers. All but the original music-only files feature video. The movies and TV shows are of near-DVD video quality, 640 pixels by 480. (DVDs are something like 704 x 480.)

That's a long way from high-def. Apple is betting that the convenience, usability, archivability, networkability, and reasonable pricing of their media content will offset the lower video resolution. Apple may be right. I can't be the only one to have noticed that 720p and 1080i/p HDTV content remains decidedly "niche" in appeal and availability, years after the HD revolution supposedly began.

Here is an article about iTV. The article includes photos, such as the one at left, of the giant screen behind Apple CEO Steve Jobs during his presentation at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts Theater in San Francisco, California on September 12, 2006.

Here is an article about iTV. The article includes photos, such as the one at left, of the giant screen behind Apple CEO Steve Jobs during his presentation at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts Theater in San Francisco, California on September 12, 2006.iTV's details are sketchy. We know that iTV:

- is a "a wireless video streaming set-top box to be released in Q1 2007."

- appears to have a footprint identical with that of a Mac mini. I assume you can stack it under or on top of a Mac mini.

- features a built-in power supply; USB 2.0 and Ethernet ports; HDMI audio/video output; optical digital audio output; RCA stereo analog audio outputs; and 802.11 (I assume 802.11g) wireless connectivity.

- is "controllable by the standard Apple remote [and] will come with an updated version of [Apple's] Front Row [software] interface that shares Front Row's smooth 3D graphics, but differs in that it has a menu on the right side of the screen."

- "works with ... iTunes on both PCs and Macs," and

- "will sell for $299."

iTV's network connectivity will allow its use as a front end to access recorded media files — movies, music, etc. — on the Internet or on a home computer network, whether wired, wireless, or a combination of the two. My particular network could build in a Mac mini, but it wouldn't need to, since I already have other Macs on a wireless AirPort network.

The iTV itself would serve as my network's video connection to my flat-panel TV, ideally via its HDMI port. It would provide an audio connection to a separate sound system, ideally via either HDMI or the digital optical audio output.

Another article about iTV appears in Wikipedia (with a link to this page offering streaming video of Jobs' full Yerba Buena presentation). The article mentions rumors "that the iTV will sport other features, such as a built in DVR feature, or even Live TV, but this is highly unlikely. Like the iPod, the iTV will start out as a mainly recorded media [gathering] device" — that is, on a home computer network.

In Media Center Mac Mini for My Bedroom? (Part 1) I looked at two TV-related Mac products from Elgato Systems, EyeHome and EyeTV Hybrid. The first of these looks like a direct competitor to iTV — whose advent will probably spell curtains for it, since EyeHome is, like iTV, a networked media-client hub. The second Elgato product, EyeTV Hybrid, offers the live TV and DVR features the Apple product apparently lacks. It is not itself network-oriented.

When you think about it, then, iTV (like Elgato's EyeHome) is all about gathering, accessing, and playing existing media content from many disparate network sources seamlessly — a worthy goal.

But the EyeTV hardware, in its Hybrid form or as EyeTV 250, is all about capturing live content piped into the home via cable or satellite or obtained over the air via an antenna. This function is one which Apple has not addressed.

iTV seems very carefully designed not to be usable as a high-def digital video recorder — by running a Firewire or USB 2.0 cable to it from, say, a digital cable box.

Some digital cable boxes (I am told) can output HD video content in digital form on Firewire, potentially allowing it to be recorded on external devices such as DVD recorders. I've never tried it, so I don't know its ins and outs. Nor have I heard of any cable boxes that output USB 2.0. But iTV is seemingly not going to be in the business of allowing digital cable-TV content to be archived on it, or even via it to its back-end computer network.

It would of course be nice if iTV could record digital 720p and 1080i HDTV programming as such. Or, if not capturing it directly on its own hard drive, at least passing it along to other computers on a home network.

But, alas, no. iTV has no intrinsic video input capability. It can retrieve already recorded video material from a home network or from the Internet, but it cannot capture live TV.

Even if an external TV-capture device like EyeTV Hybrid could be connected to iTV's USB 2.0 port, as if to enable the iTV to capture a television signal, how would the requisite EyeTV software be installed on Apple's iTV?

And even if Apple's iTV could somehow host Elgato's EyeTV software, Elgato's EyeTV hardware can't accept digital cable input ... not without the signal already having been converted to merely standard-def analog by a separate cable box.

Specifically, EyeTV lacks the ability to accept TV signals in digital form directly from the 75-ohm wire that feeds a cable box. It does not have an onboard cable-TV tuner. Nor does it accept a CableCard for decoding digital cable input. Nor does it have a Firewire input to allow it to receive a digital signal output from a standalone cable box.

In fact, Elgato tech support informs me: "There are no products for the Mac or PC that can natively decode the encrypted signal from the cable company." That's where CableCard support could come in handy. As far as I know, most or all digital cable channels are encrypted to ensure that only authorized cable boxes (or CableCards) can receive them. This includes premium channels like HBO, high-definition channels, and in fact any and all digital channels that are not part of the cable company's basic tier of service.

My own cable company, Comcast Cablevision of Baltimore County, Maryland, charges extra for all digital channels, since it basic tier channels are still all-analog. So all digital cable channels that are available to customers require decoding.

Currently, no products for either the Mac or PC will do that. That may change someday. If it does, I could conceivably make a Mac mini into the equivalent of a TiVo Series 3 HD-DVR, but with the ability to permanently archive high-def and standard-def TV content in its original form.

There's also the problem of bandwidth, though. Broadcast 720p and 1080i signals require up to 19.2 Mbps. They're only lightly digitally compressed — though cable companies typically squeeze broadcast digital channels down, bandwidth-wise, yet more.

Suppose you could somehow input 1080i at up to 19.2 Mbps into iTV and wanted to record it on a Mac mini, to which the iTV wirelessly networks via one of Apple's AirPort 802.11g products. 802.11g (also called WiFi) can run as fast as 54 Mbps, with a "typical" rate of 25 Mbps. That conceivably could be fast enough for shunting a single HDTV signal around a home network — assuming optimal wireless reception conditions. So, technically speaking, it might be possible for Apple or a third party to enhance iTV to serve as an HD-DVR — a high-definition digital video recorder.

Hence it would be nice if digital cable boxes and satellite receivers offered USB 2.0 output of their digital video signals for use by the likes of iTV. Then any digitally compressed TV signal received by the cable box might be exported into iTV, where software such as Elgato's EyeTV could capture it, either on iTV itself or elsewhere on the home network, via 802.11g.

That would be nirvana, but it's not apt to happen. Think of the copy-protection issues. Though you have a legal right to archive, for you own enjoyment and use, TV programs you legitimately receive, content providers are not about to make it easy for you. We've all heard about the "broadcast flag" that might one day be inserted into digital TV programs so you can't copy them. There are other flags in digital television that can do the same sort of thing. I've yet to hear whether, or how, they're in use today, but you can bet they'll sprout right up once a product something like iTV makes digital-TV capture simple for the masses.

Meanwhile, the prerecorded content Steve Jobs has in mind for iTV play is mainly what's available at Apple's iTunes Store. There you can now get songs, as always, plus movies, TV shows, podcasts, music videos, and movie trailers. All but the original music-only files feature video. The movies and TV shows are of near-DVD video quality, 640 pixels by 480. (DVDs are something like 704 x 480.)